SVC Occlusion with Portal Vein Collaterals

- Amara Ahmed and Kevin M. Rice, MD

- Sep 5, 2020

- 3 min read

Updated: Apr 15, 2021

Why is there contrast in the liver? • Xray of the Week

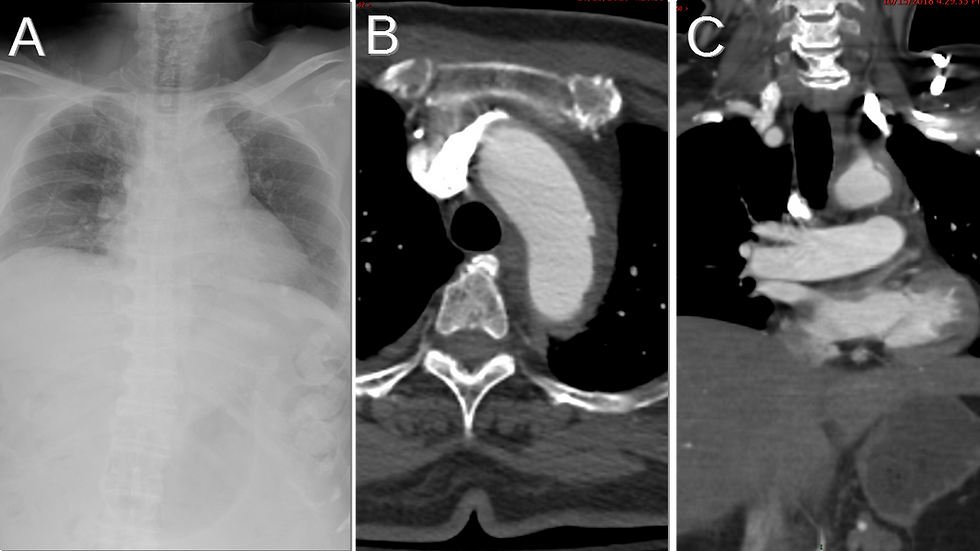

Pt with renal failure and multiple prior hemodialysis catheters resulting in SVC occlusion.

Figure 1. CT scan of patient with SVC occlusion. What is the enhancing liver lesion?

Figure 2.

A. Axial chest CT showing internal mammary vein (orange arrow), azygos vein (blue arrow), small mediastinal collateral veins (white arrow), and chest and abdominal wall collateral veins (yellow arrow)

B. Axial CT showing chest and abdominal wall collateral veins (yellow arrow), hepatic capsule and phrenic veins (green arrow) and portal vein in liver (red arrow)

C. Axial chest CT showing azygos vein (blue arrow), internal mammary vein (orange arrow), and mediastinal collateral veins (white arrows)

D. Chest and abdominal wall collateral veins (yellow arrows), mediastinal collateral veins (white arrows), hepatic capsule and phrenic veins (green arrow) and portal vein in liver (red arrow).

Figure 3. Coronal MIP CT image with thisck slab through the anterior and mid chest demonstrates the caval-mammary-phrenic–hepatic capsule–portal collaterals. Complete obstruction of the superior vena cava has resulted in a pseudolesion in segment 4.

Figure 4. Diagram illustrating caval-mammary-phrenic-hepatic capsule-portal pathway. From http://dx.doi.org/10.1594/ECR2014/C-1159

Discussion:

Superior vena cava (SVC) occlusion has multiple causes including mediastinal neoplasms, central venous catheters, pacemaker wires, aneurysms, trauma, and granulomatous diseases (1). As a result of SVC occlusion, venous drainage is maintained via collateral pathways between the SVC and portal vein (2). Four well-established collateral routes are the azygous-hemiazygous route, internal mammary vein route, thoracic and superficial thoracoabdominal vein route, and the vertebral venous plexus route (1). The patient in this case presents with SVC occlusion due to renal failure and multiple prior hemodialysis catheters. There is caval-mammary-phrenic-hepatic capsule-portal pathway-to segment 4 of the liver. Blood flows from the internal mammary vein to the inferior phrenic vein, which communicates with hepatic capsular veins (3). The hepatic capsular veins then drain into intrahepatic portal tributaries (3). This causes a hypervascular pseudolesion that can be visualized on imaging as a “focal hot spot” or hyperenhancement along the anterior portion of segment 4 of the liver (3). In nuclear studies, a warm spot near the bare area can be observed using Tc sulfur colloid (1). Along the superior aspect of the liver, there may also be focal contrast enhancement with dilation of inferior phrenic veins and hepatic capsular veins (4). Treatment involves addressing the cause of the SVC obstruction (5). Palliative stenting has been suggested as a possible treatment, but thrombosis is a common complication of this procedure (5).

References:

Rastogi R, Thulkar S, Garg R, Gupta A. Infraphrenic collaterals in malignant superior vena cava obstruction. Clin Imaging. 2007;31(5):321-324. doi:10.1016/j.clinimag.2007.04.031

Vilgrain V, Lagadec M, Ronot M. Pitfalls in liver imaging. Radiology. 2015;278(1):34-51. doi:10.1148/radiol.2015142576

Kapur S, Paik E, Rezaei A, Vu DN. Where there is blood, there is a way: unusual collateral vessels in superior and inferior vena cava obstruction. RadioGraphics. 2010;30(1):67-78. doi:10.1148/rg.301095724

Keraliya AR, Tirumani SH, Shinagare AB, Ramaiya NH. Beyond PET/CT in Hodgkin lymphoma: a comprehensive review of the role of imaging at initial presentation, during follow-up and for assessment of treatment-related complications. Insights Imaging. 2015;6(3):381-392. doi:10.1007/s13244-015-0407-z

Marini TJ, Chughtai K, Nuffer Z, Hobbs SK, Kaproth-Joslin K. Blood finds a way: pictorial review of thoracic collateral vessels. Insights Imaging. 2019;10. doi:10.1186/s13244-019-0753-3

Amara Ahmed is a medical student at the Florida State University College of Medicine. She serves on the executive board of the American Medical Women’s Association and Humanities and Medicine. She is also an editor of HEAL: Humanism Evolving through Arts and Literature, a creative arts journal at the medical school. Prior to attending medical school, she graduated summa cum laude from the Honors Medical Scholars program at Florida State University where she completed her undergraduate studies in exercise physiology, biology, and chemistry. In her free time, she enjoys reading, writing, and spending time with family and friends.

Follow Amara Ahmed on Twitter @Amara_S98

Kevin M. Rice, MD is the president of Global Radiology CME

Dr. Rice is a radiologist with Renaissance Imaging Medical Associates and is currently the Vice Chief of Staff at Valley Presbyterian Hospital in Los Angeles, California. Dr. Rice has made several media appearances as part of his ongoing commitment to public education. Dr. Rice's passion for state of the art radiology and teaching includes acting as a guest lecturer at UCLA. In 2015, Dr. Rice and Natalie Rice founded Global Radiology CME to provide innovative radiology education at exciting international destinations, with the world's foremost authorities in their field. In 2016, Dr. Rice was nominated and became a semifinalist for a "Minnie" Award for the Most Effective Radiology Educator.

Follow Dr. Rice on Twitter @KevinRiceMD

Comments